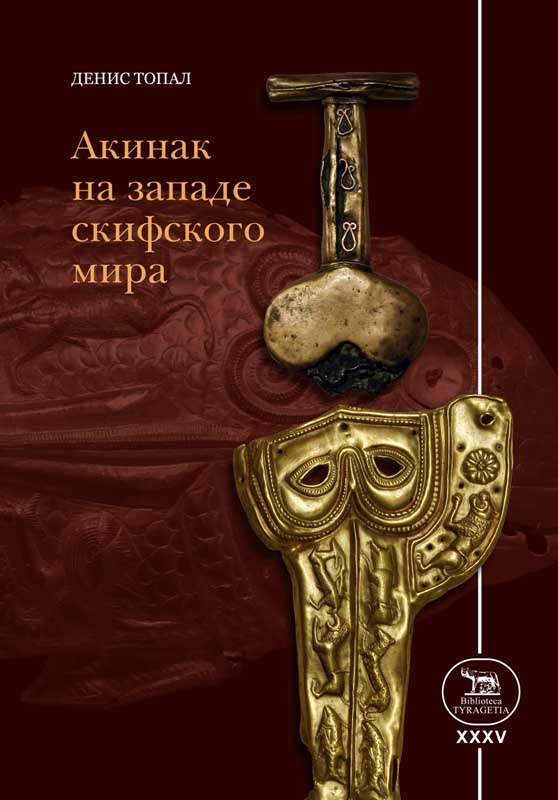

The monograph systematizes data on Scythian blade weapons from the territory of Central and South-Eastern Europe (Moldova, western Ukraine, Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland). The paper examines in detail the finds of swords and daggers of the Scythian period (more than 200 artifacts), analyzes the chronological positions of these objects based on burials, and reveals a correlation with other types of weapons. The typological features of the weapons of the early nomads are studied against a broad cultural and historical background, covering all simultaneous cultures of the Eurasian steppe cultural continuum of the Scythian period from northwest China to Silesia, including Siberia, the Volga-Urals, the Balkans and the Caucasus. Thus, fundamental changes in the morphology of the Scythian akinakes were traced, "cultural types" were identified, the sources of generation of types of the Scythian akinakes were determined, and the dynamics of the displacement of these sources in time was shown. The book is in Russian and contains 648 pages of text, 212 figures, 40 catalogue tables and 16 color plates.

Contents

Introduction

Acknowledgements

1. FROM FIRST OBSERVATIONS TO FIRST TYPOLOGIES. HISTORY OF THE STUDY OF SCYTHIAN SWORDS AND DAGGERS

1.1. 1870-1940. First observations

1.2. 1950-1980. First classifications

1.3. 1990-2010. First typologies

2. "IDEAL TYPES" OF NON-IDEAL TYPOLOGY. EURASIAN ISSUES OF THE STUDY OF SCYTHIAN SWORDS

2.1. The origin of akinakes

2.2. Dimensional groups of Scythian blades

2.3. Ceremonial swords of early nomads and akinakes from Vettersfelde

2.3.1. Ziwiye hoard

2.3.2. Oxus treasure

2.3.3. Vettersfelde hoard

3. EARLY SCYTHIAN FORMS AND THEIR REFLECTION IN THE WEST OF THE SCYTHIAN WORLD

3.1. Bronze akinakai and early Scythian scabbards

3.1.1. Gudermes type

3.1.2. Bronze akinakai of Asia

3.1.3. Posmuș type

3.1.4. Early Scythian bouterolles

3.2. Kelermes type and its "western" variations

3.2.1. Local Early Scythian forms of Carpathian-Danube region

4. MIDDLE SCYTHIAN PERIOD. SEARCH FOR NEW SHAPE

4.1. Early Middle Scythian period. Expansion to the steppe

4.1.1. Shumeyko type

4.1.2. Vettersfelde type

4.2. Final of the Middle Scythian culture. Cozia type

4.3. Nógrád type and Scythian single-edged swords

5. ANTENNAE OF SCYTHIAN AKINAKAI. EVOLUTION OF AN IDEA

5.1. Evolution of akinakai with antenna pommel

5.1.1. Representation on the monumental sculpture

5.1.2. Antenna pommels in the Early Scythian period

5.2. "Beautification" of the pommel. Găiceana type

5.2.1. Marychevka type

5.2.2. Issyk type

5.3. "Uglification" of the pommel

5.3.1. Grishchentsy type

5.3.2. Beixinbao type

6. CLASSICAL SCYTHIA AND "GOLDEN FALL" OF SCYTHIAN SWORD

6.1. Solokha type and the final evolution of the antenna pommel

6.2. Chertomlyk type and the "Indian summer" of the Scythian culture

6.3. Shulgovka type and single-edged weapons in Classical Scythian period

7. DANUBE REGION. CHRONOLOGY OF LOCAL GROUPS

7.1. Typology of cultural groups based on the weaponry

7.2. Northwest (Polish) group

7.2.1. Northwest (Polish) group

7.2.2. Tisza (Hungarian) group

7.2.3. Transylvanian group

7.2.4. South Carpathian (Wallachian) group

7.2.5. South Danube (Bulgarian) group

7.2.6. Carpathian-Dniester (Moldavian) group

7.2.7. Steppe Black Sea group (Lower Danube and Lower Dniester)

Conclusion

Bibliography

List of abbreviations

Catalogue of swords, daggers and scabbard elements of the Scythian period in the Danube region

Summary (in English)

Summary (in Romanian)

Figure captions

Colour figures