>>>

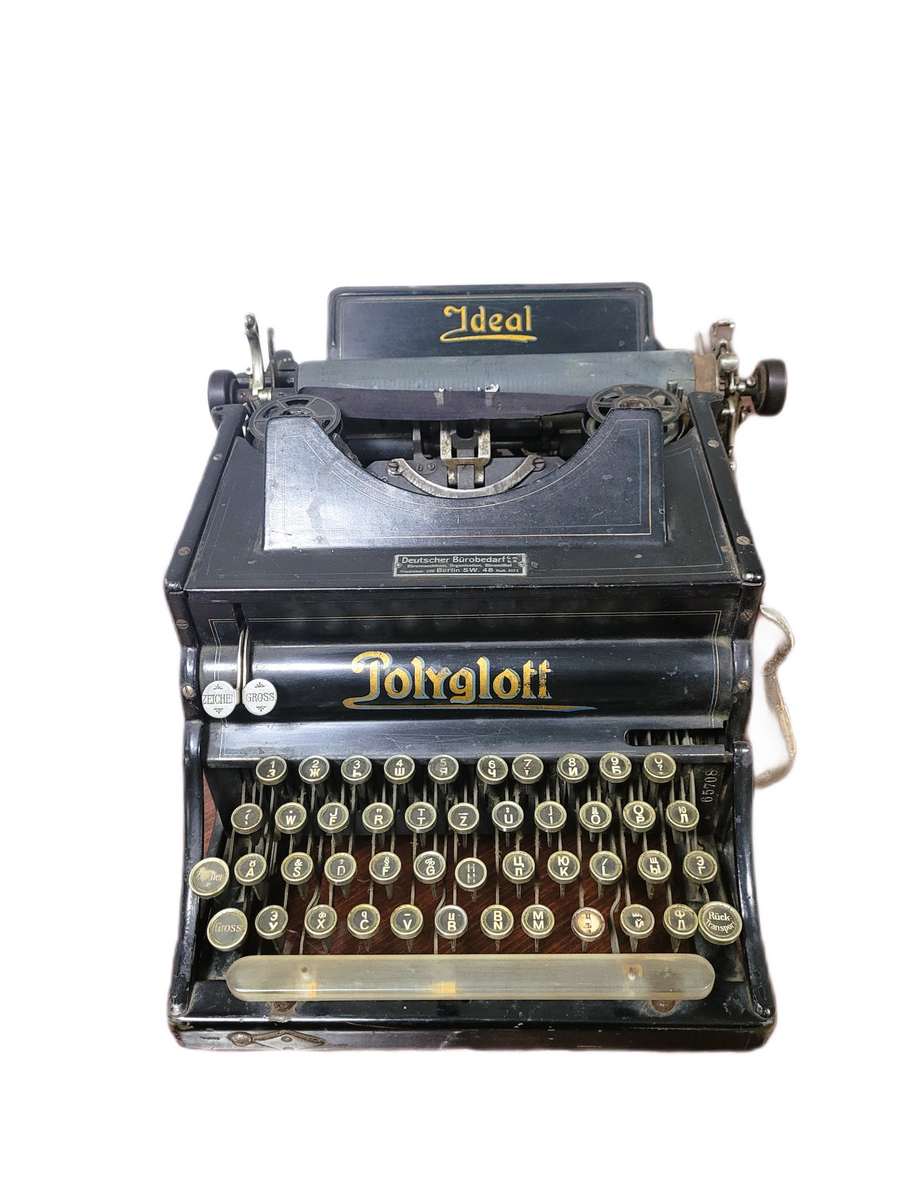

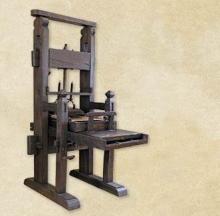

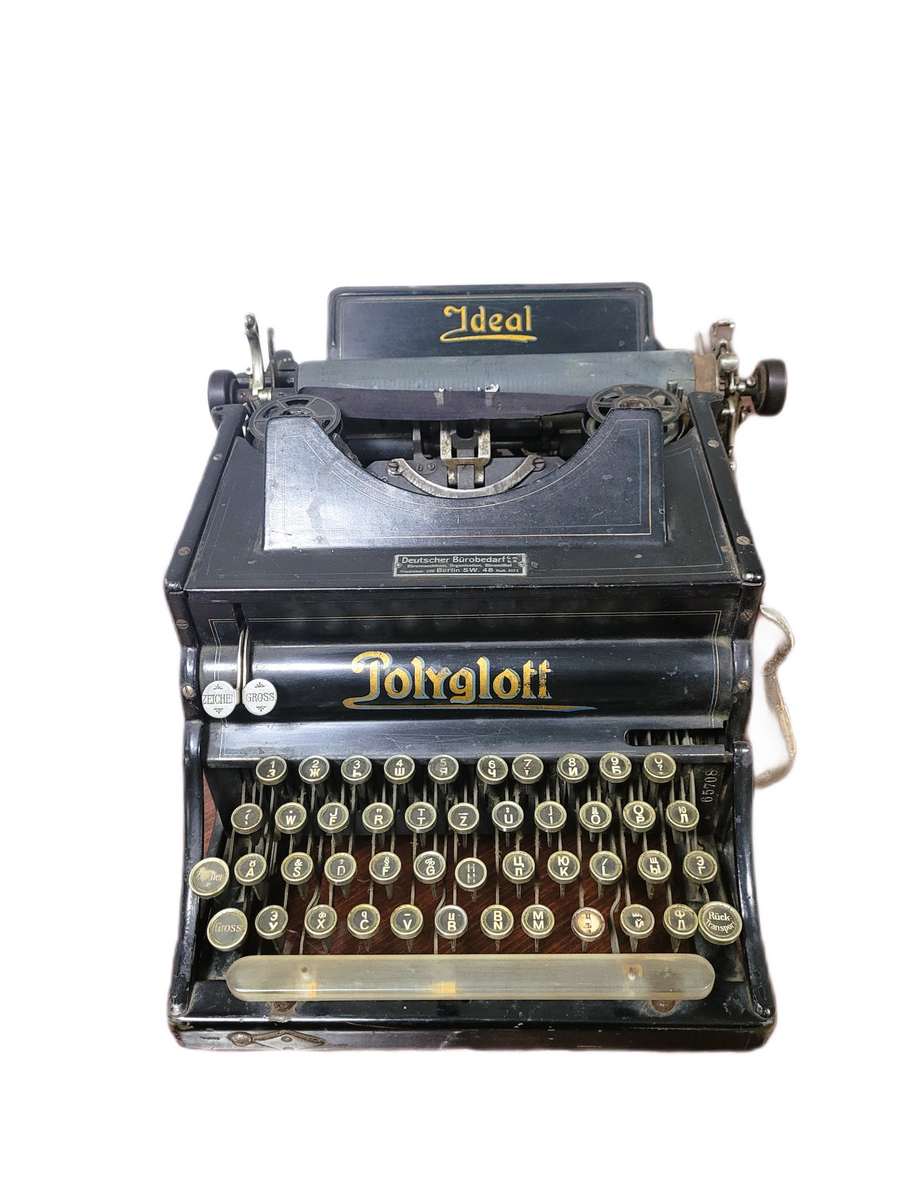

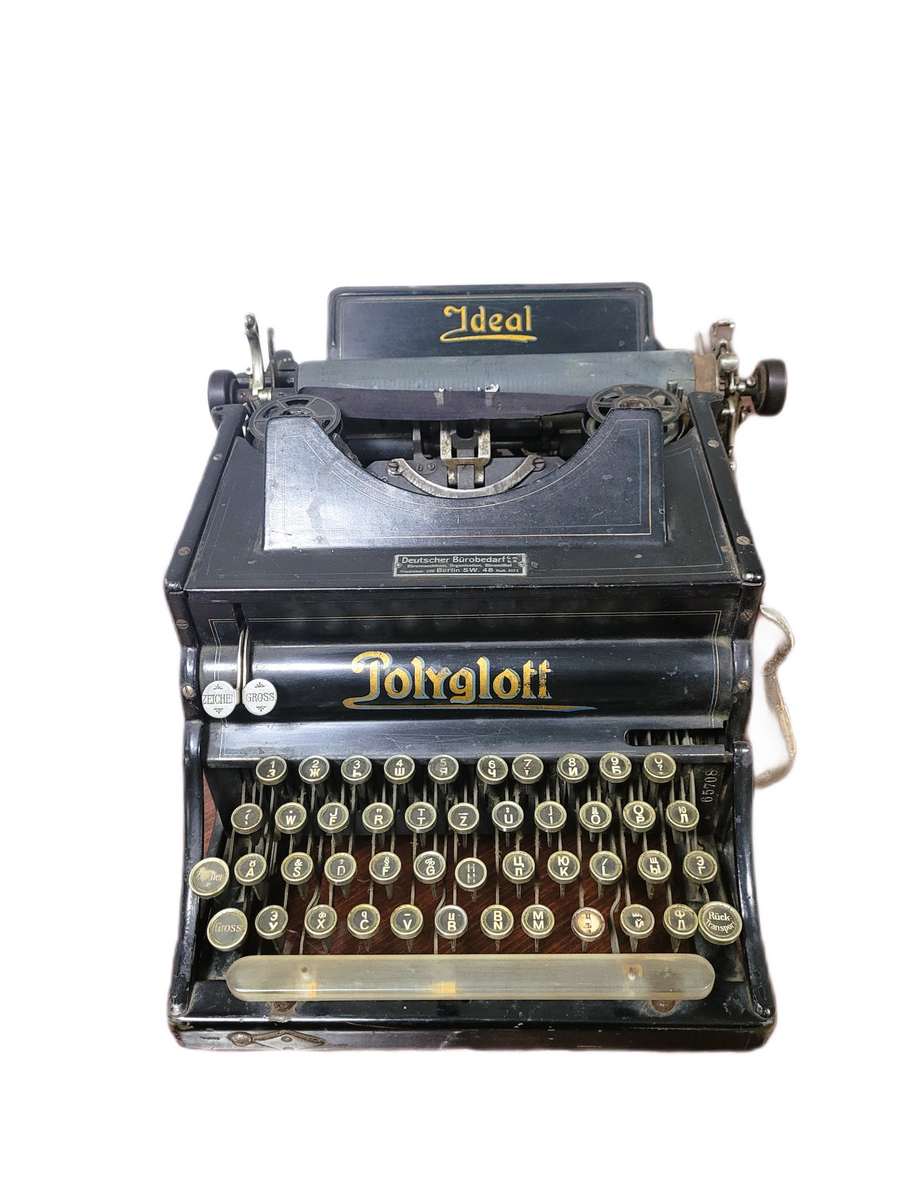

Manufactured in 1902 by AG vorm Siedel & Nauman in Dresden, Germany.

Dimensions: Length - 38 cm, Width - 35 cm, Height - 20 cm. Weight - 16 kg. It entered the museum collection in 1984, transferred from the National Museum of Ethnography and Natural History.

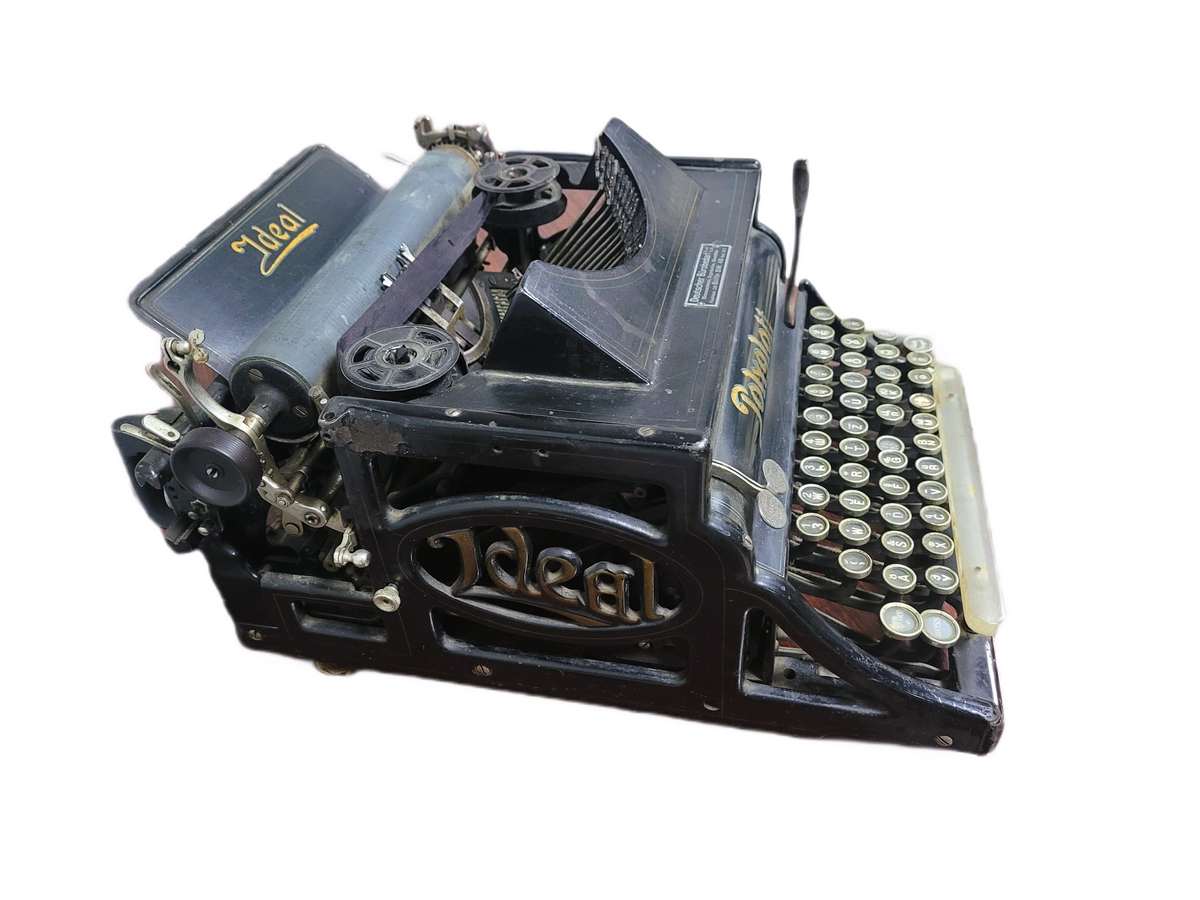

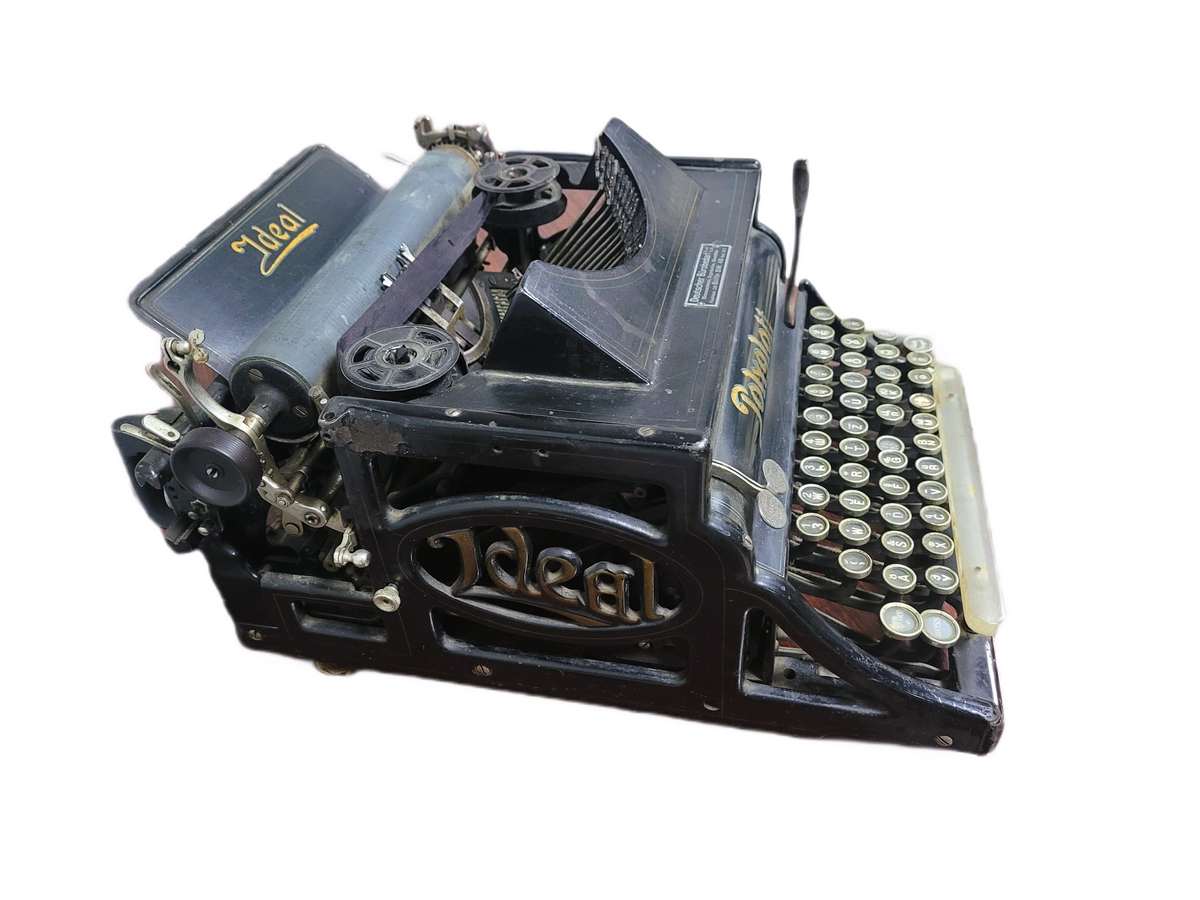

The typewriter features a standard carriage mounted on ball bearings and rollers, along with a keyboard equipped with 42 keys. These contain two complete sets of Latin and Cyrillic alphabets, punctuation marks, numbers, and mathematical symbols, enabling the typing of 126 characters. Beneath the metal casing, the type bars are arranged in a fan-like pattern, holding embossed characters and ink ribbon rollers. When the keys are pressed, the type bars strike the inked ribbon, imprinting characters onto the paper tensioned in the machine's roller system.

The side panels are elegantly decorated with refined cast-iron elements in the Art Nouveau style, displaying the brand name - "Ideal." The Polyglott model, featuring a bilingual keyboard patented in the United Kingdom by Max Klaczko from Riga, Latvia, was produced between 1902 and 1913, marking the first typewriter capable of writing in two languages. The "Ideal Polyglott" typewriter was actively sold in the Russian Empire and gained significant popularity in Poland, Bulgaria, and Serbia.

The typewriter - a mechanical device used for printing text directly onto paper - ranks among the most important inventions of the modern era, as it revolutionized communication. From the late 19th century to the early 21st century, it became an indispensable tool, widely used by writers, in offices, for business correspondence, and in private homes. The peak of typewriter sales occurred in the 1950s when the average annual sales in the United States reached 12 million units. In November 2012, the British Brother factory produced what it claimed to be the last typewriter, which was donated to the Science Museum in London.

The advent of computers, word processing software, printers, and the decreasing cost of these technologies led to the typewriter's disappearance from the mainstream market, turning it into a museum exhibit.

June 23 marks Typewriter Day, commemorating the date when American journalist and inventor Christopher Latham Sholes patented his typewriter. This day celebrates the simple yet revolutionary device that has become history, as well as the remarkable literary achievements it has enabled since 1868.

31 August 1989 St., 121 A, MD 2012, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova

31 August 1989 St., 121 A, MD 2012, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova

The side panels are elegantly decorated with refined cast-iron elements in the Art Nouveau style, displaying the brand name - "Ideal." The Polyglott model, featuring a bilingual keyboard patented in the United Kingdom by Max Klaczko from Riga, Latvia, was produced between 1902 and 1913, marking the first typewriter capable of writing in two languages. The "Ideal Polyglott" typewriter was actively sold in the Russian Empire and gained significant popularity in Poland, Bulgaria, and Serbia.

The side panels are elegantly decorated with refined cast-iron elements in the Art Nouveau style, displaying the brand name - "Ideal." The Polyglott model, featuring a bilingual keyboard patented in the United Kingdom by Max Klaczko from Riga, Latvia, was produced between 1902 and 1913, marking the first typewriter capable of writing in two languages. The "Ideal Polyglott" typewriter was actively sold in the Russian Empire and gained significant popularity in Poland, Bulgaria, and Serbia.