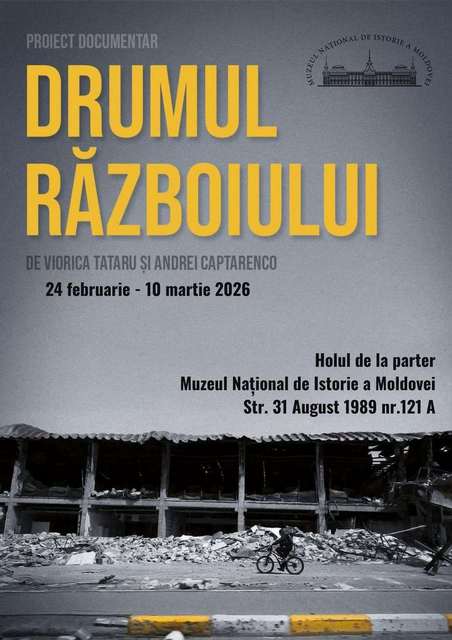

The Dniester war begins to acquire its history, its heroes and its mistakes...

The Dniester war begins to acquire its history, its heroes and its mistakes...

Like any other war, it has many secrets, darkness, madness. At first glance, it may seem that passions flared up as if out of nowhere, imperceptibly, from an innocent law of the functioning of languages.

In reality, however, it is not the linguistic confrontations, not the enmity between Moldavian Romanians and Russian-speaking people, between "nationalist" Chisinau and "internationalist" Tiraspol, "peace-loving", as the Smirnov's propaganda claims, but the struggle for the maintenance of the Bolshevik empire is at the root of the political conflict in the Dniester area, a conflict which in the early spring of 1992 escalated into a real fratricidal war.

Under the invented pretext of "defending the southern borders of Russia" political adventurers in the former metropolis encouraged Transnistrian separatism, armed guard paramilitary formations, sent thousands of mercenary Cossacks, criminals released from prisons, tanks and Alazan rockets against independent Moldova, hoping that with their help they would be able to revive lost empire.

On March 2, 1992, when the President of the Republic of Moldova Mircea Snegur delivered a speech at the plenary session of the UN General Assembly on the occasion of the admission of the Republic of Moldova to the United Nations, detachments of guardsmen and Cossacks armed with machine guns and armored vehicles stormed the Dubăsari district police department. The first fallen appeared. In the south, in Vulcăneşti, another armed group attacked the district police headquarters. The same thing happened simultaneously in Tighina, Grigoriopol and Cocieri... Among the first to die in the line of duty are: Lieutenant Colonel Mihai Moraru, Commissioner of the Hânceşti District Police Department; Iurie Bodiu, Valentin Slobozenco, Tudor Buga, Sergiu Ostaf, Vitalie Păvăluc, Viktor Lavrentsov, a Russian by nationality, a native of Tighina; Boris Dovgani from Pârâta, Serghei Culaţchi, son-in-law of the brave fighter General Anton Gămurari... The lifeless bodies of Sergeant V. Purice and driver N. Galben from Tighina were got out of the waters of the Dniester.

Civilians were attacked, entire villages were under Cossack fire, more than 50,000 civilians in the Dniester zone were forced to leave their homes to escape the scourge of war.

The ordeal that began in Dubăsari left behind hundreds of dead and crippled, orphans, widows, mothers with souls hardened by grief; it caused immeasurable material damage and loss on both banks of the Dniester.

More detailed clippings and chronicles of those dramatic events can be found in various sources: albums, monographs, collections of documents, memoirs, newspaper reports.

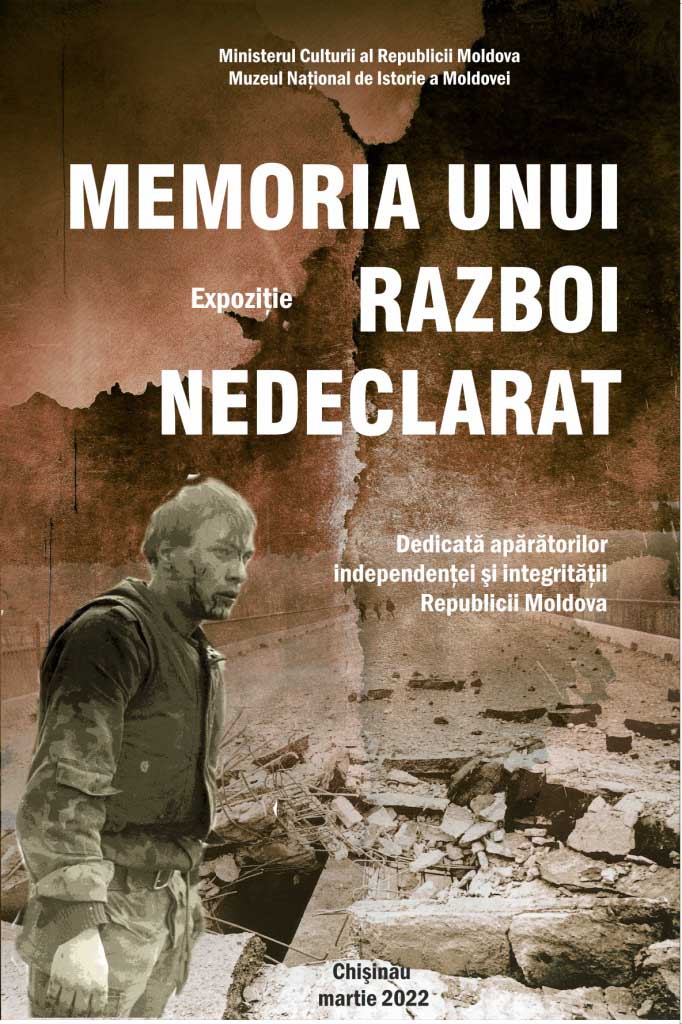

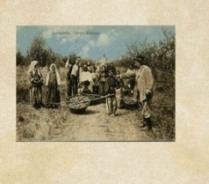

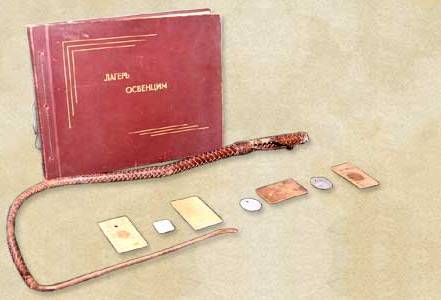

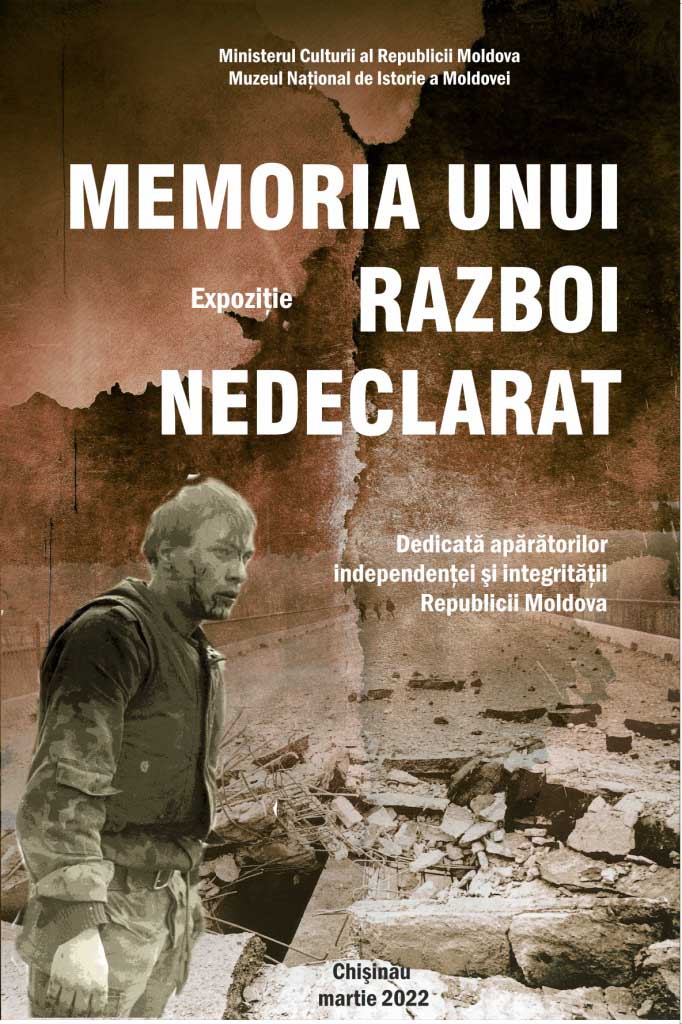

A photo-documentary chronicle of this war is also offered by the commemorative exhibition "Memory of an Undeclared War".

It was conceived as a tribute to all participants in the struggle for the defense of the territorial integrity and independence of the Republic of Moldova and, first of all, to those who sacrificed their lives on the altar of freedom of the Motherland.

The shocking pictures taken by photojournalists N. Pojoga, M. Vengher, T. Iovu, A. Mardare, S. Voronin, T. Anghel and others reflect the tragic trials that the defenders of Moldova went through in the battles of Dubăsari and Tighina, on the Cocieri and Coşniţa plateaus; they immortalized the heroism and courage of the Moldavian police and volunteers, the hardships and humiliations of the war, destroyed families, ruined houses and villages, women's and children's faces distorted by the pain of the loss of loved ones.

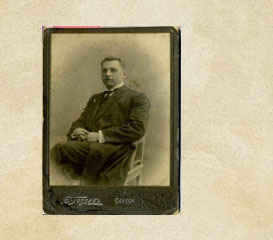

A special section of the exhibition is dedicated to the policemen who died in the fight for the independence and integrity of the Republic of Moldova.

The exhibition "Memory of an Undeclared War" was organized on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the outbreak of the armed conflict on the Dniester.