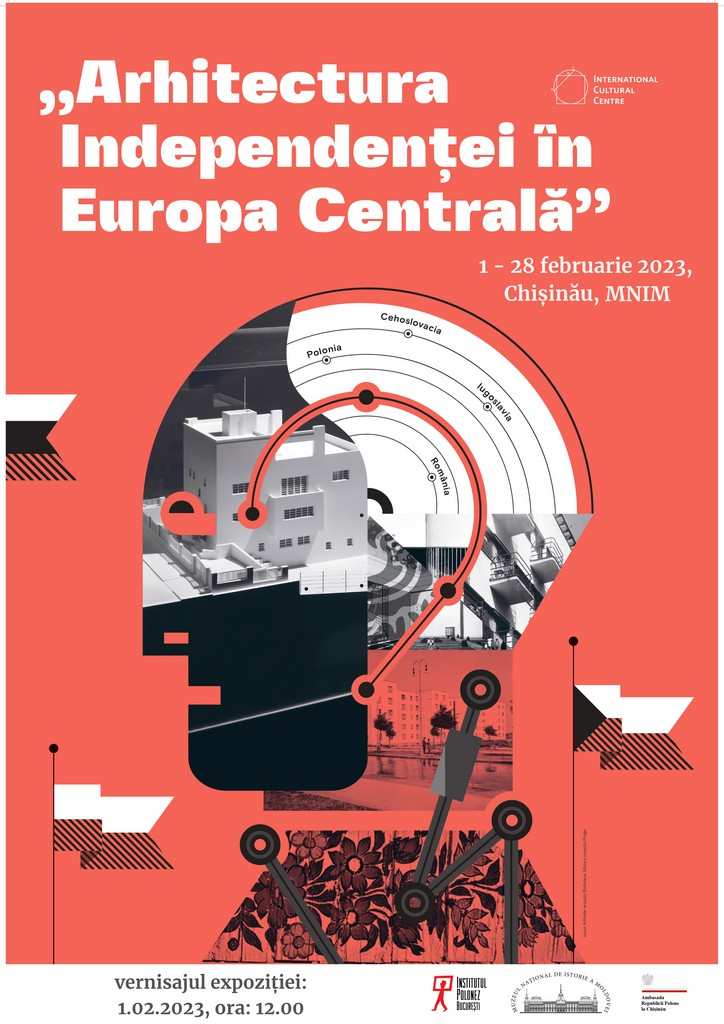

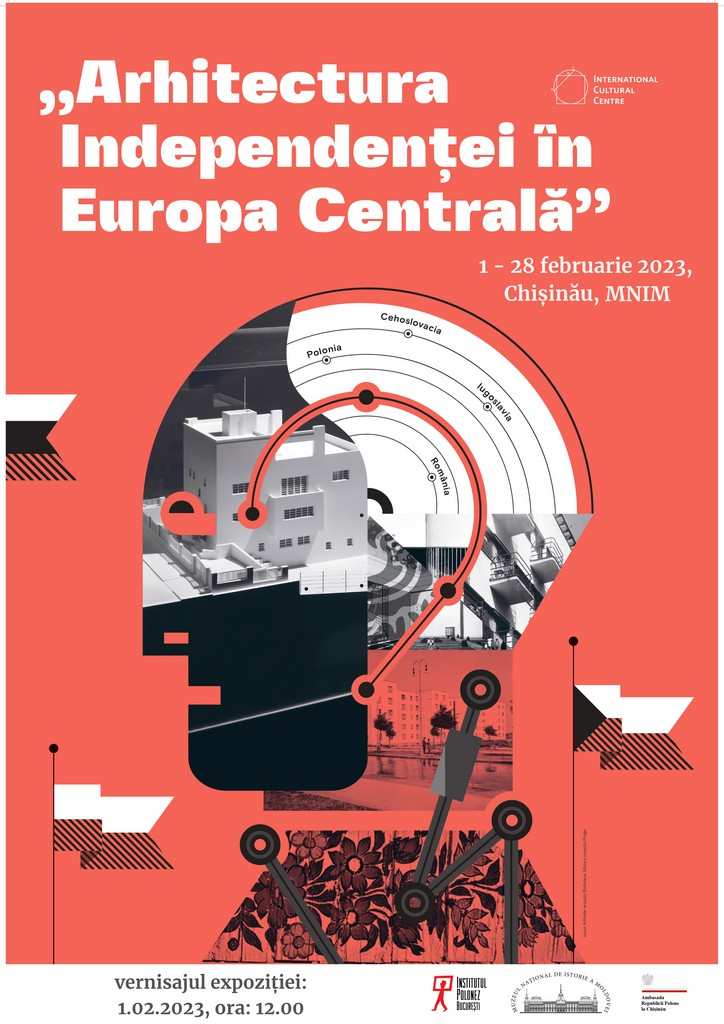

On February 1st, 2023, at 12:00, the National Museum of History of Moldova invites you to the opening of the Architecture of Independence in Central Europe" exhibition.

On February 1st, 2023, at 12:00, the National Museum of History of Moldova invites you to the opening of the Architecture of Independence in Central Europe" exhibition.

The end of the World War I in 1918 radically changed the geopolitical image of Central Europe. It brought freedom to many nations, while for others it meant profound changes to the existing framework of political and economic life. War damage, shifting borders and the clash with new political realities left their mark on the development of culture and the shape of architecture in this part of the continent in the following decades. You will discover how Bucharest, Warsaw, Tallinn, Eforie Nord and Chernivtsi have changed by reading the Romanian version of the exhibition "Independence Architecture in Central Europe" prepared by the Polish Institute in Bucharest. It can be viewed on the fence of the National Museum of History of Moldova in Chisinau from February 1 to February 28, 2023.

"It was a short but very dynamic period. A mosaic of new countries emerged on the map of Central Europe. A dream that formed after the tragedy of the First World War was to regain stability, to introduce order into the world torn apart, to find a new system for nations that finally gained their desired subjectivity" - says Łukasz Galusek, the deputy director for programme policy at the ICC and one of the curators of the exhibition. "Now, over a one hundred years later, we can look back at the moment when this new order was formed; for many, this was a time to celebrate, for others this date still provokes reflections. We look at our part of the continent in a broad horizon, trying to embrace a wide spectrum of changes happening at the time, which were reflected in space, urban planning, and architecture".

The titular architecture of independence should be understood more broadly than individual buildings. Its goal was to mark its subjectivity in the landscape of regions and cities, to search for new models of national iconography, to create opportunities for social development, as well as create an idea of a new man.

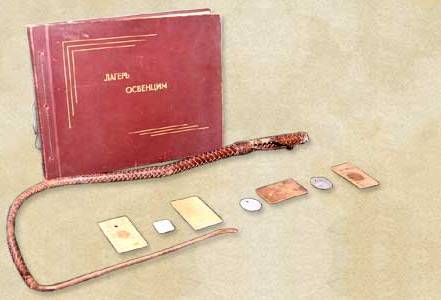

Political changes cast former lively metropolises into oblivion, while provincial towns became capitals of new states or regions. The state's authority was expressed by the monumental forms of architecture that housed its institutions - newly built or redesigned - as well as of churches and public spaces that offered scenography for the theatre of power. It was also a moment of particularly powerful presence of conflicts of memory and the problem of dissonant and unwanted heritage. Independence meant not only the creation of new national symbols, but also the destruction of marks of foreign domination and their oblivion from collective memory. Success was enjoyed by modernism, which was developed to serve the poorest groups of society (e.g., new housing estates in Vienna, Bratislava, and Warsaw), but in time gained a new, luxurious form.

After the Great War, a new idea of humanity was born. One of the most interesting visions of the man of the future was conceived in Central Europe. In 1920, a Czech writer Karel Čapek published his drama R.U.R. (Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti), with robots, biological mutants, as protagonists who rebel against people and take control over the world. Čapek's work prepared the ground for science-fiction literature, with its still resounding echo in the commonly used word ROBOT (from the old Slavic "rob" or "rab" meaning slave or servant).

The man of the future was envisioned as healthy and fit, while his body was to resemble a machine. Health and hygiene, sports and active leisure were considered factors of social and personal change as well as important vehicles of consolidation of new societies. This dynamic transformation was well illustrated by the evolution of spas and sports facilities. Sports halls, racing tracks, swimming pools, and stadiums able to accommodate thousands of viewers were a visible sign of modernisation and a perfect tool for propagandist messages communicated by the newly emerged states.

This multimedia exhibition was addressed to art viewers without any age restrictions, both to the lovers and scholars of architectural history and applied arts, as well as to those interested in cultural and social changes of the early 20th century.

The makers of this exhibition wished to show a multi-layered nature of the subject matter through the presentation of archive architecture designs, original photographs from the period, films, as well as visualisations and models of architecture designed into the 1920s and ‘30s. Maps illustrating dynamically shifting borders of countries that regained independence will be shown as an integral part of the exhibition.

The exhibition came with a series of related lectures titled 1918. The culture of new Europe, offering introduction to the history and culture of Central European countries in the interwar period, as well as an extensive programme of educational events addressed to all age groups.

Curators: Łukasz Galusek, dr Żanna Komar, Helena Postawka-Lech, dr Michał Wiśniewski, Natalia Żak.

Financed by the polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage as part of the Multiannual Programme NIEPODLEGŁA 2017-2022.