THE KINGDOM OF POLANDSigismund II Vasa (1586-1632)

Crown, thaler: 1628 (1).

Gdańsk, orts: 1612 (1), 1613 (1*), 1614 (1), 1615 (7), 1616 (8), 1617 (16), 1618 (4), 1619 (2), 161 (1), 1620 (2), 1621 (8).

THE UNITED PROVINCES OF THE NETHERLANDS

Lion thalers (leeuwendaalder)

Gelderland: 1641 (1), 1647 (2), 1649 (1).

West Frisia: 1648 (1).

Utrecht: 1643 (1), 1646 (1), 1647 (2), 1648 (1).

THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE

Kampen: halve leeuwendaalder 1646 (1), 1647 (1); leeuwendaalder 1647 (3), 1649 (1).

Zwolle: leeuwendaalder 1633 (1), 1637 (3), 1644 (1), 1646 (2), 1648 (1).

This hoard by its composition confirms the presence of silver coins from the thaler category in the Principality of Moldavia monetary circulation.

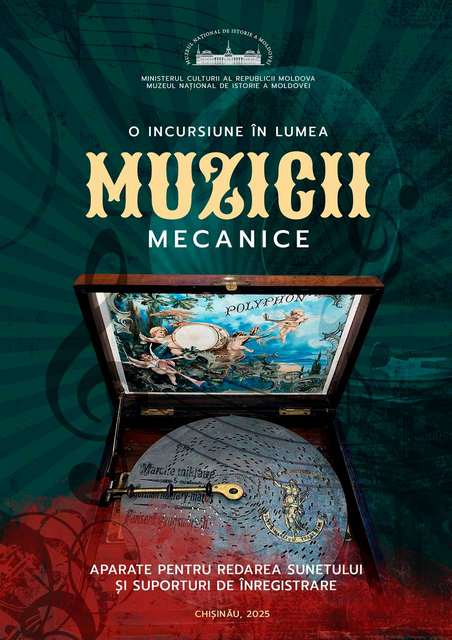

Thalers were first minted in 1486 in Sankt-Joachimsthal, today the Czech Republic, "thaler" being an abbreviation of "Joachimsthaler", meaning coin issued in Sankt-Joachimsthal. In the 16th and 17th centuries, thalers were issued in very large quantities, especially by state entities that were part of the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburg Empire. Thus, thalers can be considered a quintessentially popular coin; there are thalers of several types, such as Austrian thalers, Polish thalers, Russian thalers, Turkish thalers, Venetian thalers, also called scuzi, "reichsthalers", also called imperials, löwenthalers or lion thalers, and Spanish thalers, also called piastre. In the Romanian principalities, thalers spread widely towards the end of the 16th century, and in the following centuries their circulation became very abundant, the thaler being in circulation until the second half of the 19th century. This money was a huge success, so it is also called: daalder / daler in the Netherlands, talar in Poland, dahlar in Scandinavia, tallaro / tallero in Italy, talari in Ethiopia, dollar in America. A special category is the Dutch thaler, leeuwendaalder, löwenthaler, which means "lion thaler", also called "lion" due to the coat of arms on the reverse, which is a shield with a crown, with a lion inside; it is a silver coin minted in Netherlands, where in 1575 it was decided to mint a new coin based on the scuzi. In the Romanian principalities the lion thaler appears in the last quarter of the 16th century. These lion thaler gave the name to the currency of Romania, the Republic of Moldova (leu), and Bulgaria (leva).

Orts are also silver coins from the thaler category, equal to 1/4 thaler. A quarter thaler was originally called "ortstaler", a name that was later reduced to the form "ort" (in Old German "ort" means "a quarter"). The coin circulated in Europe in the Middle Ages, including the Romanian principalities, being met in the 18th century as Polish, Turkish and German orts. The term "ort" is preserved in the Romanian expression "to give an ort to a priest" (which means "to die"), which dates back to the ancient pagan custom of placing a coin on the little finger of the deceased's right hand so that he could pay for the passage to the afterlife; With the same coin, the priest was paid for the funeral service: the family of the deceased "gave an ort to the priest" to observe church traditions.