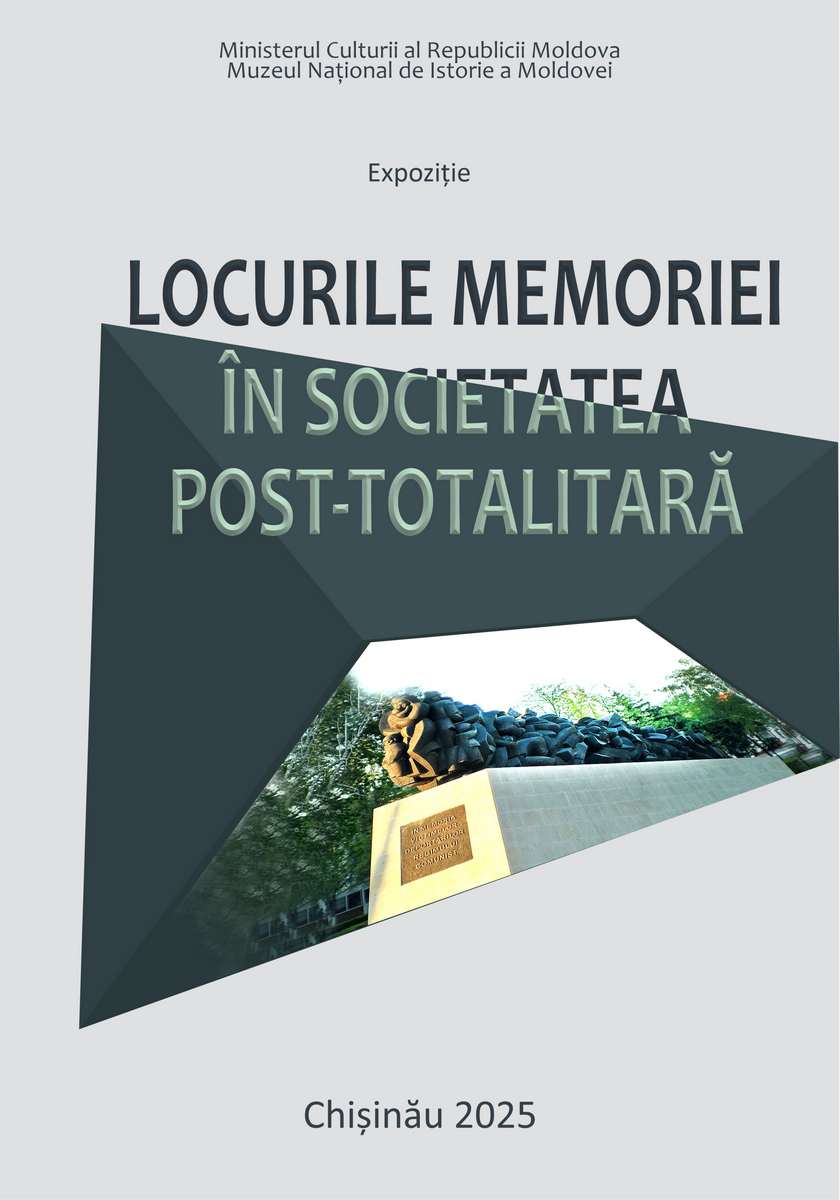

#Exhibit of the Month #Exhibit of the Month

May 2021

The copy of the golden pectoral from Tovsta Mohyla

The pectoral from Tolstaya Mogila is considered the main archaeological treasure of Ukraine (it is depicted, for example, on the logo of the Institute of Archeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine). This unique artifact of 958 gold, weighing 1140 g, was discovered as a result of excavations of the Scythian burial mound of Tolstaya Mogila (Tovsta Mohyla) on June 21, 1971 near the modern city of Pokrov (then Ordzhonikidze) in the Dnepropetrovsk region. Following the excavations carried out by Boris Mozolevsky and Yevgeny Chernenko, it turned out that a mound with a height of 8.6 m and a diameter of 70 m was filled over the representatives of the Scythian elite around 350s-340s BC. The Tolstaya Mogila mound was the family tomb of the Scythian aristocracy, in which а male burial of а "king" and then, after a short period, of a "queen" with a child was performed. Then, some time after the funeral, the burial of the "king" was robbed, but the robbers, fortunately, did not notice jewelry (a sword in a scabbard, a whip) lying in the dromos at the entrance to the tomb, including the pectoral. The pectoral from Tolstaya Mogila is considered the main archaeological treasure of Ukraine (it is depicted, for example, on the logo of the Institute of Archeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine). This unique artifact of 958 gold, weighing 1140 g, was discovered as a result of excavations of the Scythian burial mound of Tolstaya Mogila (Tovsta Mohyla) on June 21, 1971 near the modern city of Pokrov (then Ordzhonikidze) in the Dnepropetrovsk region. Following the excavations carried out by Boris Mozolevsky and Yevgeny Chernenko, it turned out that a mound with a height of 8.6 m and a diameter of 70 m was filled over the representatives of the Scythian elite around 350s-340s BC. The Tolstaya Mogila mound was the family tomb of the Scythian aristocracy, in which а male burial of а "king" and then, after a short period, of a "queen" with a child was performed. Then, some time after the funeral, the burial of the "king" was robbed, but the robbers, fortunately, did not notice jewelry (a sword in a scabbard, a whip) lying in the dromos at the entrance to the tomb, including the pectoral. It is believed that the pectoral was made by goldsmiths of Greek or Macedonian origin. It is kept in the Kiev Museum of Historical Treasures of Ukraine and belongs to the State Fund of Precious Metals and Precious Stones of Ukraine. The pectoral has a crescent shape; its composition consists of three tiers, separated by two hollow tubes in the form of a twisted rope. Two more of the same tubes frame the pectoral from above and below. The upper tier features several separate scenes with Scythians and domestic animals. In the center, two half-naked men are holding in their hands a stretched animal skin, similar to a sheep's skin. On the left and right, horses with foals and cows with calves are depicted; behind them, there are figurines of Scythian servants, one of whom is milking a sheep, and the other is milking a cow, holding in their hands, respectively, a clay pot and a small amphora. In the middle tier, among the stems of plants and flowers, there are figurines of birds. The lower tier depicts hunting scenes of fantastic griffins and real wild animals. The upper and lower friezes of the pectoral are lacy; the figurines of people and animals on them are made using the casting technique on the basis of a lost wax model. These are almost completely three-dimensional sculptures, flat only on the inside. Three-dimensional figurines of birds are attached with pins among flowers, the petals of which are covered with colored enamel. It is obvious that a certain iconographic text was encrypted in the pectoral, although its understanding is very difficult. Therefore, it is not surprising that over half a century since the discovery, more than twenty interpretations of images in the pectoral have been put forward. One of the most accurate and innovative seems to be the primary interpretation of images in the pectoral, expressed by its discoverer Boris Mozolevsky. Already in his precise, insightful analysis, the smallest details of the decor, including floral ornaments, all the movements of the figures of the lower and upper friezes, gestures and the direction of the views of the characters of the central scene are noted, although they are not always taken into account in further research. B.N. Mozolevsky also proposed an analysis of the composition of the friezes, and the interpretation of the nature of the images, especially the central scene of the upper frieze. Dmitry Sergeevich Raevsky brilliantly entered the pectoral into the conceptual model of the Scythian universe, devoting a special study to it, in which the structure of the pectoral is read as the Greco-Scythian cosmogram. The plot of the upper frieze of the pectoral can also be based on a time-varying legend associated with the emergence of the Macedonian dynasty. Therefore, the pectoral could go to the Scythian leader as a trophy captured in a clash with the Scythians in 339 BC, received as a gift during negotiations, received as a gift from Ateas for helping in the war (and he, in turn, received it as a gift when they had good relations with Philip II of Macedon). Yet much remains unclear. The pectoral has no analogies, not only in the Scythian world, but also in the Greek environment. Until now, despite the possible correspondences to its elements and techniques found in other things, the pectoral remains a special work of art, still not surpassed in the skill of execution and the lightness of the idea of its creator. The copy of the pectoral from Tovsta Mohila, an object of historical value of the Ukrainian treasury, was given as a gift to President Maia Sandu by his Ukrainian counterpart, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, during his visit to Kyiv in January 2021 and is currently part of the MNIM heritage.

|